scarecrow editorial

Tuesday, March 13, 2007

13: Offbeats & Brutalists

If you’d have asked me one year ago if a literary scene existed and was alive and most definitely kicking in London, or New York, or California . . . anywhere, I’d have laughed at the very thought. We’re still standing in that long, drawn out shadow The Beats created I would have wailed. I would have bemoaned the very nature of it (not that there is anything wrong with The Beats really – I mean, has anyone actually touched the genius of William S Burroughs since? I very much doubt it). I hate the word scene anyway. But now, one year on, ask me. Go on, ask me.

Well, it’s already happened. I think. And it seems to have happened right under our noses. And we’ve created it. It was our design. Not a marketing team in sight. We stand alone.

Well, it’s already happened. I think. And it seems to have happened right under our noses. And we’ve created it. It was our design. Not a marketing team in sight. We stand alone.

I don’t really care for names, but two seem to have immerged: The Offbeats and The Brutalists respectively. Both these movements encompass a varied and capable horde of writers. It’s funny, really, most reside in London, and most are originally from the North of England – born outsiders it seems.

"Brutalism calls for writing that touches upon levels of raw honesty that is lacking from most mainstream fiction. We cannot simply sit around waiting to be discovered — we would rather do it ourselves. Total control, total creativity. We Brutalists see ourselves as a band who have put down their instruments and picked up their pens and scalpels instead. The only maxim we adhere to is an old punk belief, which we have bastardised for our own means: 'Here’s a laptop. Here’s a spell-check. Now write a book.' " [The Brualists].

Three very determined independent publishers have immerged also: Social Disease (London)[check out their myspace page], Wrecking Ball Press (Hull – although this well established publisher has existed long before many of us picked up a pen), and Burning Shore Press (US). Each of these publishers is crucial; they take risks, they shun current trends.

Three very determined independent publishers have immerged also: Social Disease (London)[check out their myspace page], Wrecking Ball Press (Hull – although this well established publisher has existed long before many of us picked up a pen), and Burning Shore Press (US). Each of these publishers is crucial; they take risks, they shun current trends.

"[Heidi] James sums up Social Disease’s raison d’être as: “Zadie Smith is not fucking interesting”, and neither are Monica Ali and the dozens of other writers of similar social comedies that emerged in the wake of White Teeth’s huge success. “All this postmodern irony is just so dull,” James explains. “And I realised that I really hate the homogeneity of the publishing world where it’s next to impossible to get genuinely interesting work published. The big publishing houses would have you believe that there isn’t a market for new and exciting work that takes a few risks and makes a demand on its readers, but that’s bollocks. Absolute bollocks.”" [Sam Jordison, The Guardian].

As I have already mentioned before this gathering of like-minded individuals, who all eschew the current trend in publishing, have acted alone. We are elsewhere. We don’t belong. We have, more or less, turned our backs on the conglomerates; we ignore those vainglorious money-men who’d rather lunch in the stinking, laughable Groucho than sniff out new writing talent; those moronic cretins hell-bent on sales, sales, sales; we ignore marketing departments; those same bozos responsible for the horrid 3 for 2 dross in every high street bookstore; those grand panjandrums that are mostly responsible for everything that is wrong with contemporary literary fiction in this country.

As I have already mentioned before this gathering of like-minded individuals, who all eschew the current trend in publishing, have acted alone. We are elsewhere. We don’t belong. We have, more or less, turned our backs on the conglomerates; we ignore those vainglorious money-men who’d rather lunch in the stinking, laughable Groucho than sniff out new writing talent; those moronic cretins hell-bent on sales, sales, sales; we ignore marketing departments; those same bozos responsible for the horrid 3 for 2 dross in every high street bookstore; those grand panjandrums that are mostly responsible for everything that is wrong with contemporary literary fiction in this country.

The Offbeats and The Brutalists are a reactionary crowd of literary dissidents who just want to hear a new voice; we have evolved, little by little, on our own terms and have never bowed down to the conglomerates’ demands – not that they care who we are or what we do anyway. This is a new northern passage, a new way, of course it is, and it is largely due to the hard work of Andrew Gallix and A. Stevens of 3AM Magazine who have, over the last five years banged the drum for the marginalised, and have, in the process, unearthed, some of the most exciting writers of our generation.

An alternative route, a Brobdingnagian backlash of our own making, a reactionary leviathan with a sting in our tail – call it what you will.

Long live the dissenters I say!

This issue of Scarecrow is a celebration. It is dedicated to each and every one of you. Names need not be mentioned for you know who you are.

Lee Rourke © 2007

Long live the dissenters I say!

This issue of Scarecrow is a celebration. It is dedicated to each and every one of you. Names need not be mentioned for you know who you are.

Lee Rourke © 2007

For more information see >HERE<, >HERE<, >HERE<, and >HERE<.

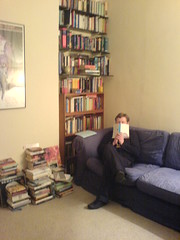

Latest Off-beat & Brutalist gathering: pictures on Scarecrow Gallery.

First to take the floor was myself [reading alongside

First to take the floor was myself [reading alongside